The capricious, cavalier manner in which Mr Trump has upset the global trade system in recent weeks has done some serious damage to the vehicle Finance Minister Nicola Willis planned to drive to a prosperous future — an export-led economic recovery.

“Going for growth” is a terrific slogan, but for it to mean anything someone actually needs to be buying what NZ Inc is selling. New Zealand stood a fighting chance of achieving that too, back when the economy of our trading partners was growing by an average 3.3% a year and some Silver Fern Farms lamb washed down by a Central Otago pinot noir was looking more and more affordable.

But then came The Donald and his tariff blowtorch. International markets have been spooked, it is now more expensive to buy New Zealand goods in our second-biggest export market, the US, and all countries are scrambling to find more accessible markets for their goods.

Treasury, in its reassuringly bland language, calls all this panic “heightened global uncertainty”.

The numbers are scary though: that average international economic growth is now forecast to average about 2%, global inflation is expected to be higher and demand for New Zealand’s goods is expected to be “dented”.

Whether “dented” means Ms Willis’ economic vehicle cops a minor fender bender or gets T-boned will take many months to become apparent. Much will depend on another word Treasury uses in such circumstances — volatility.

Undaunted, however, Ms Willis has kept the accelerator pedal down when it comes to revving up the export sector.

The main new initiative in Budget 2025, Investment Boost, is a tax incentive for businesses to splash out on machinery, tools and equipment. Firms will be able to deduct 20% of the cost of that shiny new processing chain on top of normal depreciation, in a balance-sheet adjustment which Ms Willis anticipates will be worth more to firms than a drop in the company tax rate.

She further anticipates those firms will use those machines to generate more economic activity, take on more staff, and sell their products to the world, improving the government’s books in the process.

But here is where Dodgem Donald strikes again. Price increases for New Zealand’s exports are expected to slow in coming months as global supply and demand factors “rebalance” — Treasury’s way of crossing its fingers and hoping everything works out all right.

Rural areas should be fine — dairy prices, for one, are still on the rise — but the cities where the factories, which are meant to be taking advantage of Investment Boost are largely based, are lagging behind, and tariff uncertainty adds to the worries of New Zealand manufacturers. In other words, Ms Willis’ export-driven economic vehicle is spluttering along rather than smoothly going through the gears.

Investment Boost relies, too, on many external factors for it to be a guaranteed win for the government, but in a Budget short of ground-breaking initiatives it should play well to the base of each of the governing parties.

That lack of a sure fire spark plug and the flickering influence of the US president is reflected in the operating balance forecasts: the government’s books are predicted to return to surplus in 2029, but by such an anaemic amount that it will be a close run thing as to whether it can be achieved or not.

The good news for Ms Willis is that inflation is expected to remain at about 2% and that interest rates are expected to keep falling: they are the two main indicators households and businesses care about and they are in her favour.

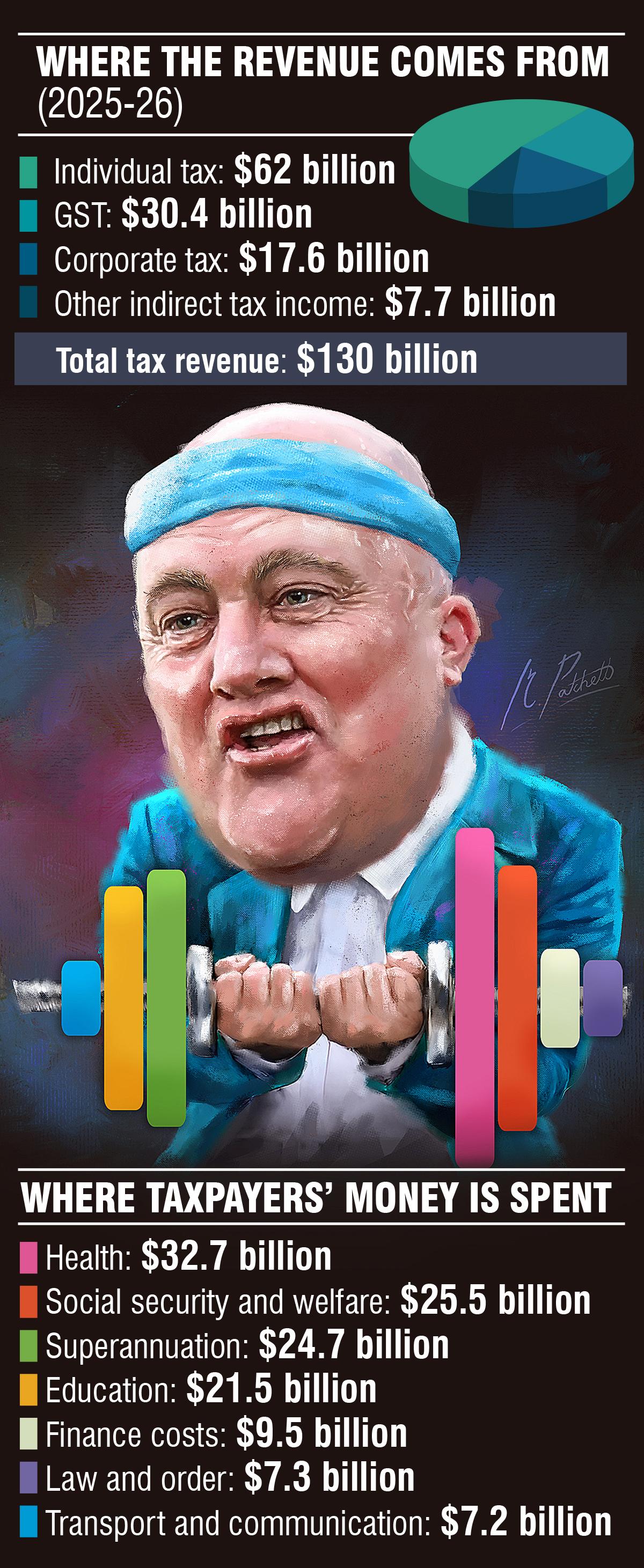

The bad news is that tax revenues are soft, debt remains high and there are three more years of Mr Trump still to be navigated.

mike.houlahan@odt.co.nz