Survivors of abuse in state care who have been sent to prison as adults are devastated by a proposed redress law change which could exclude some from getting abuse compensation.

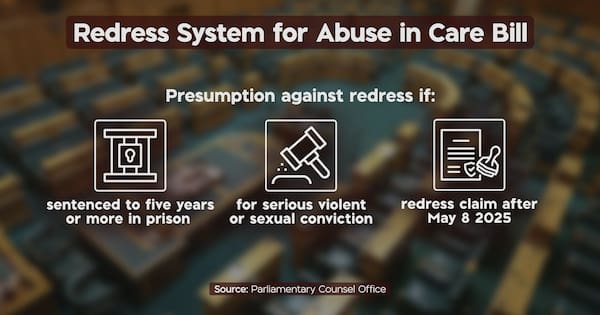

The Redress System for Abuse in Care Bill, which passed its first reading this week, would introduce a presumption against financial redress for survivors if they have been sentenced to more than five years in jail for serious violent or sexual offending, and filed their redress claim on May 9 2025, onward.

It’s estimated 5% of survivors have become serious offenders later in life, with the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care identifying a “care to custody” link, due to violence and disconnection inflicted on youth.

For state abuse survivor Rawiri Waretini-Karena, he was regularly beaten in foster homes and boys’ homes for 12 years.

Then a fight gone wrong landed him with a murder conviction in his teens, after he fought and killed a man wrongly identified as a child abuser.

“When I went to prison, I was a teenager. I’d never been there before but when I got there, I recognised the majority of them… It’s because we all grew up in state care together,” he told 1News.

Despite the abuse Waretini-Karena he suffered in state care, he has never sought financial redress, and now has a PhD after a 30-year career in education and social work.

But he is shocked other survivors, who want to seek financial redress, could now miss out.

“It’s kind of like pulling the rug out from under them,” he said.

Cooper Legal lawyer Lydia Oosterhoff said these people would be “punished twice for offending”.

“So the first punishment they’ve obviously taken, they’ve paid their debt to society through a sentence of five years. And then they’re punished a second time because they are being denied redress from the state that abused them.”

Survivors could appeal to an independent redress officer to appeal their exclusion, under the law, if they can argue their case does not put the redress system into “disrepute”.

There will also be fines of up to $5000 for people who fail to declare their convictions.

But Crown Response advisors warned Cabinet earlier this year that the Redress Bill may be inconsistent with the Treaty of Waitangi Article 3, because it may have inequitable outcomes for Māori who are over-represented in the justice are care systems.

The Royal Commission found at least 200,000 children were abused in care between 1950 and 1999 in Aotearoa and as many as 1 in 3 have been later incarcerated.

Survivor advocate Eugene Ryder is one of them, but he has already been paid redress and is not impacted by the legislation. He felt the bill was unfair – focusing only on offending of survivors, not the way they were victimised first.

He told 1News: “If you think about the abuse that survivors suffered, they were actually criminal acts and if it was a person instead of the state, then they [the state] would likely be imprisoned.”

In a boys’ home, Ryder joined a gang for protection from horrific assaults he had endured.

Oosterhoff said there were many stories like this among survivors, and under the new bill, “the government is targeting people who the state in essence, largely created”.

“I think it’ll be very devastating,” Ryder said.

“Regardless of what they became as a result of that child abuse, we can’t deny that it happened,” Ryder said.

The average state redress payment is now $30,000.

But the Royal Commission found the average lifetime cost of lost health and productivity for survivors was more than $850,000 each.

In a statement Minister Erica Stanford said: “The Bill in no way, is intended to diminish the abuse and/or neglect that those survivors suffered.”

Instead, she said the bill aimed to make sure, that paying survivors who became offenders “does not bring the state redress system into disrepute”.

If someone requests to have their denial of financial redress reviewed, Stanford said it “will be up to the independent decision maker who will be appropriately qualified to take the decision”.

“If initially declined, the survivor will be able to reapply to have their case reconsidered after three years. This provides an incentive for the survivor to rehabilitate and a further opportunity to obtain financial redress if they wish.“

She has declined 1News’ interview requests on the redress plans every week for the last month.

The bill passed its first reading on Tuesday and is now going to Select Committee.